For reasons of sense where without it there’d be none, the leaflet handed to visitors explaining the Frieze floor-plan showed its likeness to a chessboard. The fair’s bread and butter existence borrows yet more from the grandest of strategic games – oligarch takes (the entire contents of) f5; a former King surrenders; an opening hostile move here; an exchange of significant pieces there.

Following its 1996 defeat at the hands of Grandmaster and then world champion Garry Kasparov, an updated version of Deep Blue, IBMs supercomputer built with the aim of showing the triumph of cold calculation over reasoned agility, caused Kasparov just a year later to rapidly wilt under its HAL-like omnipresence in the deciding game of their rematch. The man versus machine contest was possibly the greatest aesthetic intervention in the history of anything, with an outcome that posed more material questions than legitimate art has ever dreamt of addressing.

Not that an artwork could ever rival the depth of collective research, vast budget and specialist knowledge poured into ensuring software claimed the finest chess scalp, but neither were IBM in the position of those artists who, when parading a new toy, must sell it to stay afloat; just as well, as paintings, sculptures and the like more innocently take up office or home space than a retail line of Deep Blues running Mind Control Version Inevitable Logic ever could. Luckily for humanity and the art world, Frieze has become the slickest selling machine.

No longer open on Sundays and with a hike in general admission ticket prices, the move to catering to commerce rather than the public pays high dividends at the market’s outer reaches. With premium stands costing up to £100’000 a day, exhibitors need a return as much as those represented. With some galleries making 80% of their annual income over the fair’s brief duration, priority is given to buyers rather than observers. London’s very own White Cube aren’t likely to argue – passing on Damien Hirst’s ‘Because I Can’t Have You I Want You’ for £4’000’000 eases the blow of the post-Sunday lunch crowd missing out on a peek by having to walk off their excesses elsewhere.

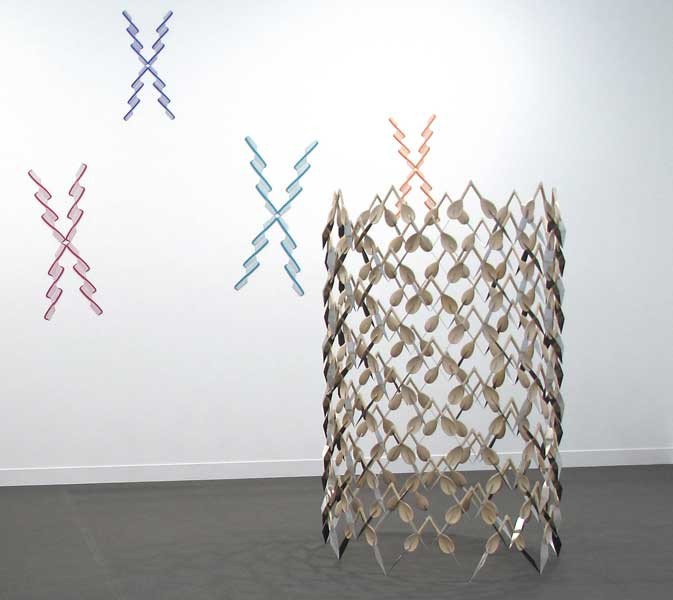

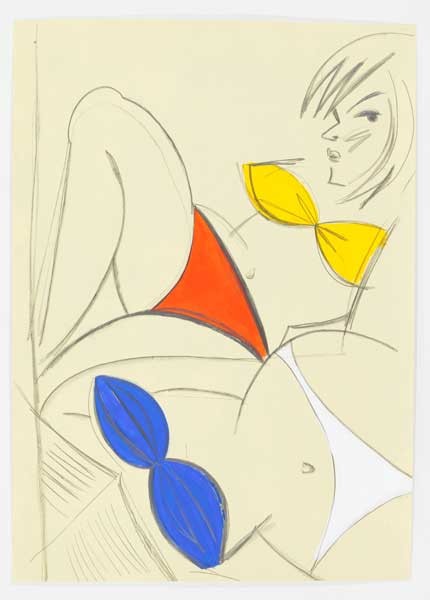

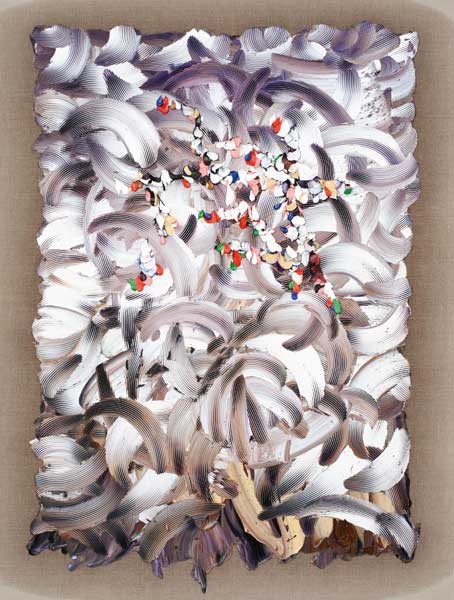

Back in the almost real world, Zander Blom of Cape Town’s Stevenson smartly applied paint with sculptural precision to the linen backdrops from which his pieces ruptured from, Ella Kruglyanskaya of New York’s Gavin Brown’s enterprise – by turning English seaside-town postcard humour into her muse – produced gorgeous scenes of retro titillation and Ana Prada of Madrid’s Galeria Helga de Alvear merged objects commonly used alongside one another for a shared purpose into a form unfamiliar to both, but whose entwined embodiment these common utensils behaved naturally in. However, the show’s highlights came in the shape of the immersive performance pieces included in the debut Frieze Live category, as these works’ various engagement points challenged the audience as much as those setting price on a representation no longer fixed and transferrable within the object itself.

In Adam Linder, Berlin’s Silberkuppe handed their area’s control – or at first appearance what suggested a lack of it – to a dancer trained at London’s Royal Ballet School and past participant with Michael Clark’s Company, so that along with fellow performers Justin Kennedy and Jonathan P. Watts his taste for the skewed presented a choreographic service there and then or at any other time or place anybody may fancy. Who knows whether hiring the mini-troupe to cavort around your chosen venue, whether pub toilet or bus to work in a contrast to the normal business expected and still concurrently happening there, is money well spent.

As Linder and Kennedy reacted to Watts’ criticisms of the rest of Frieze, written on paper then stuck to their booth’s walls, by one silently slithering and writhing around the crowded but, once the piece began, quickly dispersing area as another read aloud the oblique criticisms for his partner to translate into dance – or certainly movement – their opinion on this was as much disguised as onlookers could not conceal their discomfort with the strange thing occurring in their private space Linder and co. easily ignored. ‘Some Proximity’ turned the tables on viewers pressing their noses up against a work. Here it was thrillingly shoved up our own nostrils.

Ante Timmermans of Zurich’s Barbara Seiler delivered the show’s checkmate move by again channelling the most primitive urge to fill walls, from Stone Age cave paintings to today’s graffiti, with sentiments, messages, jokes, threats, signs, symbols or crudity, then pushing this trajectory further than Linder. In ‘) pause (’, the booth’s walls are covered in text drawings referring to the stage directions of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting For Godot, an absurdist play in which nothing happens, twice, should we miss its absence at the first time of asking. These instructions have been torn from their ordinary habitat so can no longer meet their objective of guiding actors on a theatre’s stage, rendering dramatisation in those terms impossible.

Throughout Frieze’s duration, five alternating dancers, though not Timmermans himself, carried out without pause and in any sequence they wished, paying no heed to how the other performers chose to begin, the specific orders of the texts. Minus dialogue, which none of them contained, the nonsense aspect of Beckett’s work was celebrated. Timmermans’ work demanded we consider lack, or the deliberate removal, of that which we believe is fundamental to our practices. What are we left with? Does expression suffer from the loss of a component? Is Timmermans a director or manipulator, if they’re not the same thing anyway? The disjunctive themes explored here conversely brought together the exhibition as a whole.

Timmermans also boldly showed what Frieze itself had been lacking. With founders Amanda Sharp and Matthew Slotover handing over responsibility for next year’s edition, it’s hoped that the emergent arts continue to expand future shows while its practitioners develop the space art responds to.

Paul Stewart